BY: Nikos Tsafos*

PEJOURNAL – This was a tumultuous summer in the Eastern Mediterranean. On August 12, there was a collision between a Greek frigate and a Turkish frigate as the two navies circled the Turkish survey vessel Oruc Reis. Military exercises drew in forces from the United States, Russia, and France. The United States, Germany, and NATO each tried to mediate between Greece and Turkey. The Mediterranean members of the European Union held a summit, leading French president Emmanuel Macron to tweet “Pax Mediterranea” (whatever that means).

Russia offered to help lower tensions, and Greece announced a massive weapons procurement program. And while Greece and Turkey have started to talk again, the prospects for a deal are low, with no clear end in sight.

Everyone understands that this rise in tensions is linked, somehow, to energy. The natural gas discoveries made since 2009 have elevated the region’s importance in the global energy map. But few can articulate what this conflict is about, why it has gushed onto the front stage so quickly, and how energy might be linked to it. Fewer still have good ideas on how to diffuse it—besides calling for “diplomacy,” “de-escalation” or “dialogue,” or casting blame on Greece or Turkey (depending on where one stands). There is an urgent need to unpack this conflict, to understand what the parties are quarreling over, and how energy impacts those conflicts. Without it, no de-escalation is possible.

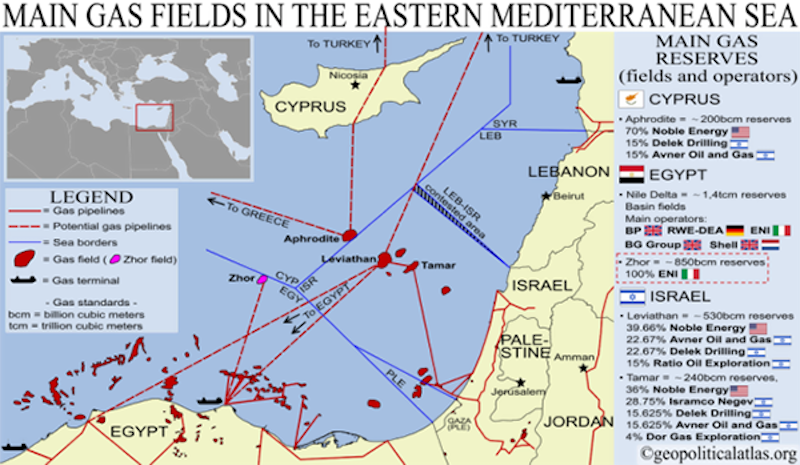

This is not a “conflict over energy resources” in any normal way of defining the phrase. The waters where Greece and Turkey deployed naval forces this summer are hundreds of miles away from the known discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean. None of those discoveries are disputed either—they are entirely within the exclusive economic zones (EEZ) of Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt. (One field in Cyprus, Aphrodite, extends into Israel’s EEZ.) There are places around the world where states claim the same resource, and those competing claims lead to tension or conflict. Not so in the Eastern Mediterranean.

It is similarly a misnomer to speak of one, discrete “conflict.” When tensions flare up in the Eastern Mediterranean, they do so for different reasons, in different areas, and among different parties. There are disparate claims based on various legal or political arguments. Details are often blurred in the interest of telling a story, but in doing so, conflicts are lumped together in a way that confuses the uninitiated. That is unnecessary. There are several conflicts, and it is easy to separate them: there is one conflict involving Cyprus, and another over the role of islands in the delimitation of maritime zones. Both conflicts have several dimensions and interact with a broader political and geopolitical environment.

The Conflict over Cyprus

The conflict over Cyprus relates to unresolved status of the island. Turkey has protested any effort made by the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus to engage in exploration or exploitation of resources within the Cypriot EEZ; that is, to sign maritime delimitation agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, and Israel; to license blocks; to enter into agreements for development, etc. These protestations are made “on behalf of” the Turkish Cypriots, which Turkey considers “co-owners” of any hydrocarbons in Cyprus. Without their consent, Turkey views any actions taken by the Republic of Cyprus as illegal and prejudicial to the rights of Turkish Cypriots.

In principle, everyone agrees that Turkish Cypriots should benefits from hydrocarbons—this is the position of the U.S. government and of the Greek Cypriots. But translating that principle into practice is hard. Under what basis will revenue be shared? What kind of consultation is appropriate without an overall settlement for the island? How can the rights of the Turkish Cypriots be safeguarded if decisions are made by, and the revenues accrue to, the Greek side? These questions are thorny. They are also, largely, theoretical. None of the three discoveries made in Cyprus since 2011 is being developed. There is no revenue to split, and no timeline for its arrival. But the prospect of revenues is enough to cause tension.

There is another angle to the Cyprus conflict. The Republic of Cyprus has issued licenses off the southern coast of the island, but the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which is recognized only by Turkey, has issued licenses not just in waters off its coasts, but also in the south, in areas that overlap with licenses granted by the Republic of Cyprus. (Those licenses have all gone to TPAO, the Turkish state petroleum company.)

The assumption is that both communities in Cyprus speak for the whole island, and the Turkish Cypriots have an equal right to issue licenses around the island. TPAO has sent ships to those areas, causing tensions. In a narrow sense, this conflict is about who can invite others into the Cypriot EEZ—hence, it is another dimension to the question of Cypriot sovereignty and the status of the island.

The Conflict over Maritime Boundaries in Mediterranean Sea

The second set of conflicts is over maritime boundaries and the influence of islands in claiming a continental shelf and in creating an EEZ. These conflicts all involve Turkey and either Cyprus or Greece. Turkey’s position is that islands, under international law, have no automatic right to a full EEZ—their influence might be reduced, even to zero, when doing so will lead to a more “equitable” outcome. Turkey believes that its long coastline should entitle it to a sizable EEZ in the region and that granting a full EEZ to various islands would be “unfair.” From this starting point come three conflicts.

The first maritime conflict is over the Greek island of Kastellorizo, which is the easternmost island of Greece, far from other Greek islands, and adjacent to the Turkish mainland. When Turkish officials present legal precedents for their positions on islands, most of their cases deal with instances similar to Kastellorizo: small islands far away from the mainland or other islands and close to another country. The Greek starting position is that all islands generate a full EEZ; for Turkey, a full EEZ for Kastellorizo is a non-starter because it grants Greece a big EEZ in the Eastern Mediterranean and Turkey a small one.

The second maritime conflict is with Cyprus. Turkey’s syllogism is similar as with Kastellorizo, except that Cyprus is bigger than Kastellorizo, and Cyprus is also an island state, as opposed to an island away from some mainland. The Turkish position is, again, that its vast coastline should be more important than whatever EEZ is generated by Cyprus in order to ensure “fairness.”

And while Turkish officials ground their positions in international jurisprudence, there is rarely a clear basis for this position (the closest analog in the usual slide deck presented by Turkish officials is the delimitation between Libya and Malta, where Malta’s influence was reduced in drawing the midpoint, but Cyprus is 30 times bigger in landmass than Malta). On that basis, Turkey has issued licenses for exploration in areas that reside in the EEZ claimed by Cyprus.

The third maritime conflict also involves Greece and emerged from the delimitation agreement signed between Turkey and Libya in November 2019, which expanded the areas that Turkey claimed as part of its continental shelf. The westernmost point in the delimitation agreement is about 50 nautical miles south of the Greek island of Crete, but 150 nautical miles away from the closest point on the Turkish mainland (which, in a straight line, crosses Greek islands; to avoid crossing any Greek islands, the distance is closer to 190 nautical miles). Here, Turkey applied its argument about Kastellorizo to bigger Greek islands like Crete and Rhodes, denying their effect in creating an EEZ. The continental shelf that Turkey now claims almost touches Crete.

Most of the confrontations this summer—the areas where the Turkish seismic ship Oruc Reis was deployed, where the Turkish and Greek navies faced each other—have been to press the claim in the first maritime dispute near Kastellorizo. This is not to say that such a dispute can be isolated from others, or that this is the only flashpoint, since Turkey continues to also deploy vessels in the two areas that form its dispute with Cyprus (the areas where TPAO has licenses granted by the TRNC, and those that Turkey and Cyprus claim as within their continental shelf). But it is important to where the recent tensions were concentrated.

The maritime conflicts between Greece and Turkey are also often lumped together and mixed with the “Aegean Dispute” that date backs to the 1970s. Politically and diplomatically, these conflicts are linked. But the substance of the dispute is different in the Aegean, where Greece and Turkey are arguing over the territorial waters that each island might be entitled to, about who governs the airspace and who has responsibility for search and rescue missions, about how the continental shelf might be divided, about the sovereign status of several islands, and about the demilitarization of Greek islands that are near the Turkish coast.

The two sides also disagree on what topics are up for negotiation—to simplify, Greece takes a narrow view about what should be on the table and Turkey an expanded one, sometimes wanting to also discuss issues relating to the presence of a Muslim minority in Thrace in Greece.

What Changed?

It is easy to try to explain the conflict as rooted in “deep-seated rivalries” or as a reflection of “decades-old” disputes. It is similarly possible to look for deeper root causes: the breakdown in Turkey’s accession to the European Union, stalled talks over Cyprus, efforts by Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan to deflect from economic troubles at home, and so on. All these factors are important. But there are two overriding developments that help explain the current moment we are in.

First, there has been a vacuum created by a disengaged United States has turned the conflicts in Syria and Libya into free-for-alls. Other states have seized the chance to press their interests. The conflict between Greece and Turkey entered a new phase when Turkey intervened in Libya to support the government in Tripoli and secured a maritime delimitation agreement; it was to this move that the Greek delimitation agreement with Egypt responded this summer.

France and Turkey have quarreled over Libya, and part of France’s support for the Greek position can be traced to that dispute. Egypt and Turkey are also on opposite sides of the Libyan conflict, although their bilateral disputes run deeper than Libya, to include, for example, the role of Islam in politics. A sense that the geopolitical cards are being reshuffled in the region has prompted states to try to reposition themselves and defend their interests, creating tension.

Second, the energy developments in the region have largely excluded Turkey, a fact that has angered Turkey. That anger is mostly unwarranted. There are plenty of reasons, commercial and political, for the discoveries to be developed without including Turkey.

In press releases and presentations, the companies involved have always showcased a range of alternatives, but shipping the gas to Turkey was never high on their list (nor, for that matter, was the East Med pipeline; more on that below). Perhaps this was due to the challenge of laying a pipeline across waters that might be contested or might be caught in conflict. There was a commercial logic too, given the intense competition to supply Turkey. Why try to squeeze gas in among so many competitors?

But energy was a basis for a number of bilateral and multilateral linkages that mostly left Turkey out. Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and the United States established the “3+1” structure to discuss areas of possible cooperation. From Washington, a renewed emphasis on the Eastern Mediterranean as a strategic anchor coincided with worsening relations with Turkey over a number of issues, including defense systems and Syria.

The Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum emerged as place for everyone to come together and talk about gas—everyone save Turkey. And the East Med gas pipeline, despite making limited commercial progress, continues to make headlines with political statements of support, aggravating Turkey by reinforcing the impression that it is being left out of the energy game (and also by promising to cross waters that Turkey claims belong in its continental shelf).

What Next?

How to de-escalate this situation? A broader fix is unlikely any time soon: there are too many conflicts, too many warring parties, too many fronts, and too many outside powers elbowing each other. It will take years for a new equilibrium, and it probably requires an end to the wars in Libya and Syria.

The conflict between Greece and Turkey can be seen in the same light: one could hope for a wide-ranging agreement that resolves the issues over which the two sides have sparred since the 1960s; or, one can aim for a relaxation in tensions, a pledge to keep disagreements from flaring up, or better yet, an agreement on what issues should be discussed and by what diplomatic or legal process. If there is an opportunity for a broader agreement, one should aim for that. But there is no need to wait until that moment happens.

To diffuse tensions, it is helpful to face some facts, even if only tacitly rather than publicly. The first is that the East Med pipeline is unlikely to be built—the economics have always been challenging, and low energy prices coupled with an accelerating energy transition in Europe make the pipeline even less likely today.

The second is that the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum cannot be a productive regional body without Turkey—but inviting Turkey can only happen if the members feel it is willing to play a constructive role. And the third is that it is unlikely the disputed areas between Greece and Turkey will hold hydrocarbons or that those hydrocarbons will be of great value—so there is no harm in waiting for a while. This impression has been reinforced by recent news that all eight wells that Turkey has drilled in the Eastern Mediterranean, some in disputed areas and some not, have come up dry.

On their own, these facts cannot produce a de-escalation. Greece, Cyprus, and Israel cannot abandon the East Med pipeline in a way that appeases Turkey. Turkey is unlikely to refrain from sending ships into disputed areas as long as it sees other states advancing projects that it sees as undercutting its interests. And there is little reason for either Greece or Turkey to say out loud that there is probably nothing of value in the areas that both claim as theirs to exploit.

But a deal can be made between these propositions: a reversion to a status quo ante, a willingness to delay action in favor of dialogue, and a willingness to take each other’s interests into account, remembering that, in the end, these conversations are largely immaterial, and the energy facts on the ground have already determined much of what will happen in this region.

The United States has a central role to play in such a negotiation. As both Greece and Cyprus are members of the European Union, it is hard for it to present itself as an honest broker, especially since different countries see the conflict differently. Russia is already trying to exploit this fog, offering to step in.

The United States has stuck to a tight script but not enough to lower tensions. A strong relationship with the United States is something both Greece and Turkey value, and U.S. mediation has always been an essential ingredient in avoiding conflict between the two for decades. Grounding diplomacy on hard energy facts—understanding that there is less at stake than the parties think, less to win, and less to lose—that should make it easier for the two sides to pull back from their positions without losing face and without surrendering anything substantial while committing themselves to a substantive dialogue. The time for U.S. leadership is now—before it is too late.

*Nikos Tsafos is a senior fellow with the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

This Commentary is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).