BY: Anke Hassel*

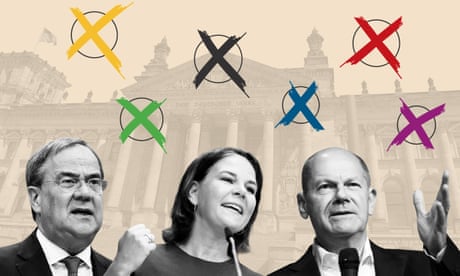

PEJOURNAL – German Federal election ended an astonishing campaign run, unprecedented in the country’s postwar history. Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union party experienced a landslide defeat, not only losing about a quarter of its vote share, a number of important constituencies – including the one that Merkel herself held – but also ending up in third place in three of the eastern states of Germany, behind the Social Democrats and the rightwing, populist AfD.

Since 2015, the Christian Democrats have gone from being the dominant force in German politics, almost invincible and the only remaining dominant party or Volkspartei, to a party in disarray, with major internal power struggles, depleted of policy ideas and rocked by corruption scandals, with CDU politicians found to have made personal gains from the pandemic through controversial mask deals.

The Social Democrats, largely written off as a serious contender for the election only six months ago, saw a remarkable comeback, finishing first in the popular vote and gaining substantial support in the eastern states. Their candidate, experienced finance minister Olaf Scholz, presented himself as the true heir to Merkel’s political style, combining rational thinking and personal modesty.

Both parties have lost their status as dominating political forces; neither could attract more than 26% of the vote, and each need two more parties to form a government. The Greens and the liberal Free Democrats (FDP) are kingmakers and can side with either the Conservatives or the Social Democrats. These are not natural allies, as the FDP’s selling points are market liberalism and fiscal austerity, while the Greens are closer to the Social Democrats on fiscal and social policy and propose that a strong state is necessary to deal with the climate crisis.

Both parties, however, agree on other points. Both are keen to push for innovation and digitalisation, but also human rights and migration. Despite being fiscally hawkish, the FDP is very friendly towards the EU and favours further steps towards a closer union. On climate change, the FDP favour more market-based instruments, which the Greens do not oppose. Both would agree that Germany’s best contribution towards solving the climate crisis would be to become a leader in climate-friendly technologies, provided by the highly successful German Mittelstand of small and medium-sized businesses and the country’s engineering base.

The Green party’s candidate, Annalena Baerbock, paid many visits to the business community during the election campaign, with at least some companies appreciating her understanding of the problems facing them, and her support for solving them. There is substantial common ground in both parties regarding the need for policy fostering technological solutions to current challenges.

The green/liberal force also represents a generational shift in German politics. Among first-time voters, the FDP scored first place with 23% of the votes; the Greens came second with 22%. The former Volksparteien, the CDU and the SPD, meanwhile, lagged far behind. Their electoral support is with elderly people, who represent 30% of the electorate. Both big parties try to woo older people with pension policy and also by promising to retain the status quo.

If the green/liberals are now in the driving seat, this is a challenge to the dominance of older people in the policy making of previous governments. The SPD has already started to recruit younger MPs; about a third of the newly elected MPs are under 40. Within the CDU, a move exists to break the monopoly of older politicians, such as Wolfgang Schäuble, former finance minister, who are seen as responsible for choosing Armin Laschet, viewed as a hopeless candidate with low approval ratings.

The biggest challenge for a pragmatic coalition government focused on the future is to find sustainable compromises on thorny issues. In a three-way coalition, key policy positions need to be hammered out before the government takes office.

Austere fiscal policy and balanced budget rules will constrain public investment in innovation and necessary infrastructure. The three parties will have to come up with new ideas to mobilise public investment, either through an investment fund or through the reallocation of existing subsidies for new investment.

Market solutions for fighting climate change are likely to exacerbate social inequality and might drive up prices for mobility and housing. Germany fears popular discontent against climate policies if incomes are affected. Finding mechanisms to compensate lower-income households for the higher costs that climate policies will incur is a policy priority.

Finally, on Europe, the new government will have an important say on the European fiscal framework and the prospects of the EU’s Covid recovery fund. Here, the influence of the Green/FDP parties should strengthen European decision-making despite the hawkish position of the liberals.

As the smaller parties figure out who they would choose as chancellor, the message that will come from the new government is already taking shape: Angela Merkel is passing the baton to a younger generation of politicians, who are less attached to the older parties of the centre-left and centre-right. The new chancellor will come from one of the old parties; the policies, however, will be shaped by the young.

*Anke Hassel is professor of public policy and co-director of the Jacques Delors Centre at the Hertie School, Berlin