BY: Chaitra Arjunpuri

PEJOURNAL – Ever wondered why India’s measure to ban China related apps and cancellation of Chinese contracts given for infrastructure development is praised and backed by other countries? China’s lending and investment policies, often disguised as help, in other countries have always resulted in “hidden debt” trap. This trap has pushed the economies of the borrowing countries to a worse than expected slowdown, one of the many problems associated with it.

Over the past 20 plus years, China has become a major global lender, with outstanding claims exceeding over 5% of global GDP. It has given many loans to developing countries which was hitherto unknown, creating a “hidden debt”. The picture of how many, how much do countries around the world owe China and under which conditions is not clear. “In total, the Chinese state and its subsidiaries have lent about $1.5 trillion in direct loans and trade credits to more than 150 countries around the globe. This has turned China into the world’s largest official creditor – surpassing traditional, official lenders such as the World Bank, the IMF, or all OECD creditor governments combined,” notes research published by Harvard Business Review.

Some analysts call this a “debt-trap diplomacy”. China offers cheap loans for infrastructure development and smaller economies face a great threat when they’re unable to pay back the interest to their lender. The best example is what happened in Hambantota, Sri Lanka. The Mattala International Airport, financed through Chinese loans and built by Chinese companies, has been dubbed as “the world’s emptiest international airport”. Over the past decade, China has held Sri Lanka in a debt-glut that will take at least a couple of generations for the island nation to repay.

China ‘Belt and Road Initiative’

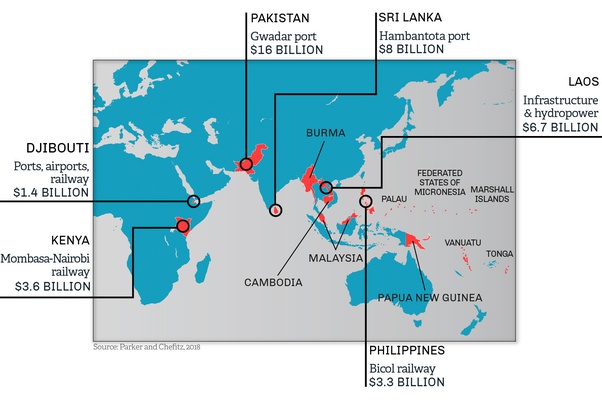

China wants to become a global trade leader and developing countries need funds to develop transportation infrastructure, and this situation leads to a win-win situation for both. China has burdened several poor and developing countries across the world with debt through its “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), a colossal infrastructure investment plan to build rail, road, sea, and other routes sprawling from China to Central Asia, Africa, and Europe. Belt and Road, or yi dai yi lu, is a “21st-century silk road”, confusingly made up of a “belt” of overland corridors and a maritime “road” of shipping lanes. This multi-billion multi-billion-dollar expansion project to expand its power around the world by lending funds is also called the “Chinese Marshall Plan”.

In 2013, Xi Jinping launched this BRI project to improve the infrastructure around Asia, Africa, and Europe in exchange for global trade opportunities and economic advantage. The project plans to invest in various 60 projects around the world, exceeding $1trillion, while the actual costs might be even higher. “Chinese financial institutions have provided more than $440 billion in funding for Belt and Road projects,” said Yi Gang, the Governor of People’s Bank of China, during a talk at the second Belt and Road Forum in Beijing last year.

China lends funds through its two policy banks – the China Development Bank, and the Export-Import Bank of China. The Export-Import Bank of China has provided “more than $149 billion in loans to more than 1,800 Belt and Road projects”, while the China Development Bank has provided “over $190 billion for more than 600 Belt and Road projects since 2013”.

The BRI’s projects in strategically-located developing countries have been criticized as a debt-trap tactic by critics and media in Western countries, India, and Africa, as the loan terms are secretive and the interest rates are very high. For instance, in 2006, Tonga took a loan from Export-Import Bank of China to rebuild infrastructure. The country was unable to repay the interest and suffered a debt crisis in 2013-2014, and the loans claimed a whopping 44 percent of Tonga’s GDP.

Though there is a large amount of overseas lending, there is no official data regarding debt flows and stocks. China does not report anything about its international lending. Their loans literally fall through the cracks of traditional data-gathering institutions. Credit rating agencies like Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s; data providers like Bloomberg focus on private creditors. China doesn’t come under their monitoring, as its lending is state-sponsored. Besides China is neither a member of the Paris Club, an informal group of creditor nations, nor of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Both the Paris Club and the OECD collect data on lending by official creditors and China is again out of their screening.

China’s overseas debt stocks and flows worldwide “includes nearly 2,000 loans and nearly 3,000 grants from the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949 to 2017”, according to researchers, who used the data from hundreds of primary and secondary sources, put together by academic institutions, think tanks, and government agencies, including historical information from the CIA.

Countries caught in the trap

Most Chinese loans have financed large-scale investments in infrastructure, energy, and mining in several countries. It has a significant influence and investment in African countries. African countries “owed China $10 billion in 2010” and it rose to “$30 billion by 2016”, according to research conducted as part of the Jubilee Debt Campaign in 2018. Currently, five countries in Africa owe the largest debt to China – Angola with $25 billion, Ethiopia with $13.5 billion, Zambia with $7.4 billion, the Republic of Congo with $7.3 billion, and North Sudan with $6.4 billion.

While South Africa owes an equivalent of 4% of its annual GDP to China, Nigeria owes $3.1 billion of the country’s total US$27.6 billion foreign debt, Zambia owes $7.4 billion of the country’s total $8.7 billion of debt, Republic of Congo owes $2.5 billion, and Djibouti owes total 77% of the country’s total debt to the Red Dragon. In fact, Djibouti has to pay back over 80% of its GDP to China to clear its loan and in the process became a host to China’s first overseas military base in 2017.

Kenya borrowed a loan of at least $9.8 billion from China between 2006 and 2017 to build various infrastructure in the country, and the Chinese debt accounts for 72% of overall foreign debt. In 2019 Kenya was at a stage to lose its control over its largest and most lucrative port, the Port of Mombasa, as it failed to repay the loan. It had borrowed over $6.5 billion from China to build a standard gauge railway between Mombasa and Nairobi, and highways in Kenya.

With a desire to taming the desert, China is financing Egypt to rebuild its new capital Cairo. The construction is expected to take 15 years, costing more than $11 billion. Gen. Ahmed Zaki Abdeen, who heads the Egyptian state-owned company overseeing the new capital, lambasted the US reluctance to invest in the land of pyramids in an interview, “Stop talking to us about human rights. Come and do business with us. The Chinese are coming – they are seeking win-win situations. Welcome to the Chinese.”

Chinese investment in Latin America is rapidly increasing and analysts have warned about the debt-trap diplomacy and neo-colonialism. While Ecuador had to agree to sell 80-90 percent of its crude oil to China in exchange for $6.5 billion loans, Argentina was denied access and oversight of a Chinese satellite tracking station in its own land. The scene in Venezuela is much worse and an article published by Carnegie-Tsinghua Centre For Global Policy said that China’s loans to Venezuela are “lose-lose” financial mistakes where both countries lose.

Not just African and Latin American countries, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Malaysia, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Papua New Guinea are caught in the Chinese debt-trap in Asia. Export and Import Bank of China gave a loan to Sri Lanka to build the Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port and Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport at an annual interest rate of 6.3%.

When the island nation was unable to repay the loan, it had to lease the Port, built at a cost of $361 million, of which 85% was funded by China, to the Chinese state-owned China Merchants Port Holdings Company Limited for 99 years in 2017. This move not only caused concern in the neighboring countries like India and Japan but also in the US that the port might be used as a Chinese naval base to threaten its geopolitical rivals.

“It’s a reminder BRI is about more than roads, railways, and other hard infrastructure,” said Jonathan Hillman, director of the Reconnecting Asia Project at Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “It’s also a vehicle for China to write new rules, establish institutions that reflect Chinese interests, and reshape ‘soft’ infrastructure,” he added.

The tentacles of the Chinese debt-trap have even entrapped countries in Europe. Italy was the first major European economy to sign up for BRI, also known as China’s Silk Road program. Officially, more than 20 countries in Europe, including Russia, are part of this initiative. China is financing the expansion of the port of Piraeus in Greece and is building roads and railways in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and North Macedonia.

A report from the European Commission in March said that the third of the EU bloc’s total assets are owned by non-EU companies, of which “9.5% of firms had their ownership based in China, Hong Kong or Macau – up from 2.5% in 2007”. The Chinese foreign direct investment in the EU rose to $48.6 billion in 2016. The Rhodium Group and Mercator Institute noted that “a large proportion of Chinese direct investment, both state and private, are concentrated in the major economies, such as the UK, France, and Germany combined”.

An analysis by Bloomberg last year said that “China now owned, or had a stake in, four airports, six maritime ports and 13 professional soccer teams in Europe”. It also estimated that “there had been 45% more investment activity in 30 European countries from China than from the US”, since 2008. There’s no doubt China is gaining its ground in Europe, whether through direct investments or through BRI.

Hidden risks

The Red Dragon has been an active international lender since the 1950s. When it started lending loans to the other Communist states, it “accounted for a small share of world GDP, so the lending had little or no impact on the pattern of global capital flows”. But today, its ending is substantial across the world. While official entities such as the World Bank typically lend loans at a concessional, below-market interest rate, and longer maturities, China lends at market terms, and the interest rates are close to private capital markets. Furthermore, its loans seek collateral warranty. Debt repayments are secured by commodity exports in exchange for the loan.

Debt accumulates very fast for the bowing economies. “For the 50 main developing country recipients, we estimate that the average stock of debt owed to China has increased from less than 1% of debtor country GDP in 2005 to more than 15% in 2017”, says the Harvard Business Review research. Among these, Djibouti, Tonga, Maldives, the Republic of the Congo, Kyrgyzstan, Cambodia, Niger, Laos, Zambia, Samoa, Vanuatu, and Mongolia owe a debt of at least 20% of their nominal GDP to China.

Beijing “encourages dependency using opaque contracts, predatory loan practices, and corrupt deals that mire nations in debt and undercut their sovereignty, denying them their long-term, self-sustaining growth,” said US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson on March 6. “Chinese investment does have the potential to address Africa’s infrastructure gap, but its approach has led to mounting debt and few, if any, jobs in most countries,” he added.

Analysts also note that 50% of China’s loans to developing countries go unreported. The debt stocks do not appear in the “gold standard” data sources provided by the World Bank, the IMF, or credit-rating agencies. Such unreported lending from China “has grown to more than $200 billion as of 2016”.

In addition, there’s one more hidden factor behind this loan lending. China is making its presence felt in the global finance through its growing network of “swap lines” by the People’s Bank of China. The bank signs swap agreements with the central banks of the borrowers to exchange their currencies to facilitate trade settlements. Till 2018, the People’s Bank of China had “signed swap agreements with more than 40 central banks”, ranging from Argentina to Ukraine, providing the “right to exchange more than $550 billion of their own currencies for Chinese currency”, the renminbi or RMB.

Subsequently, nations burdened by the debt and financial crisis turn to China instead of the international financial institutions like the IMF to swap their currencies. Since 2013, Argentina, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russia, and Turkey have swapped their currencies with RMB during market distress.

Above all, the loans hid the collateral interference with the borrowing country’s economy, allowing China to gain strategic advantages. Almost all the ports and other transport infrastructure built with the Chinese funds could be used either for commercial or military purposes. “If it can carry goods, it can carry troops,” noted Jonathan Hillman.

The investment and presence of China in other countries have been steadily increasing with its own hidden agenda. Its investment in countries like Africa and Venezuela is not just to gain global political influence, but also to secure a solid base of raw materials to fuel China’s own rapidly growing economy. Africa is rich in natural resources and it contains 90% of the entire world supply of platinum and cobalt, 75% of the world’s coltan – an important mineral used in electronic devices, including cellphones, half of the world’s gold supply, two-thirds of world’s manganese supply, and 35% of the world’s uranium supply.

Brahma Chellaney, in a 2017 article for Project Syndicate, explained that Chinese loans are “collateralized by strategically important natural assets with high long-term value, even if they lack short-term commercial viability. For example, the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka straddles Indian Ocean trade routes linking Europe, Africa, and the Middle East to Asia.

The African continent is a strategical spot for China to extend its geopolitical influence. China is already a major power in Asia and as India is its historical rival, it has no other go but to look for a realistic choice in undeveloped countries of Africa to expand its global presence and influence in the world.

There’s little doubt that China is now a significant player in not only Asia and Africa, but also in Europe, through direct investments or through its BRI project. Many countries in the BRI project have started to rethink about the perils of the investments and the hidden clauses for delay of non-payment of the funds to China. Governments getting ever more cautious towards Chinese investments, particularly in sensitive sectors of the economy like telecommunications and defense. The best example is India which recently banned not only 59 Chinese apps in the country, but also canceled several contracts and tenders given to the Chinese companies to develop infrastructure facilities.

As more and more countries in the world continue to fall into the debt-trap of China pushing the future generations to economic captivity, the classic ‘Same Script, Different Cast’ by Whitney Houston and Deborah Cox has never rung truer. Only the time has to say whether China will ever put an end to its monopolistic way of lending loans and creating debt-traps in the poor economies around the world.