BY: Navomee Ponnamperuma*

PEJOURNAL – In recent months, China has come under much scrutiny for its policies, starting from their mismanagement of the current global pandemic to the renewed hardline approach taken towards Hong Kong. Amidst the chaos, many in the West have overlooked the economic stronghold China has been building in the South Asian region, thanks to President Xi Jinping’s project of the century, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A project that certain academics refer to as China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’.

Contrary to Western institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, China offers a form of ‘cash for resources’ scheme. As such, in exchange for financing and building infrastructures in poorer countries, China requests ‘favorable access’ to the receiving state’s natural assets, from minerals to ports.

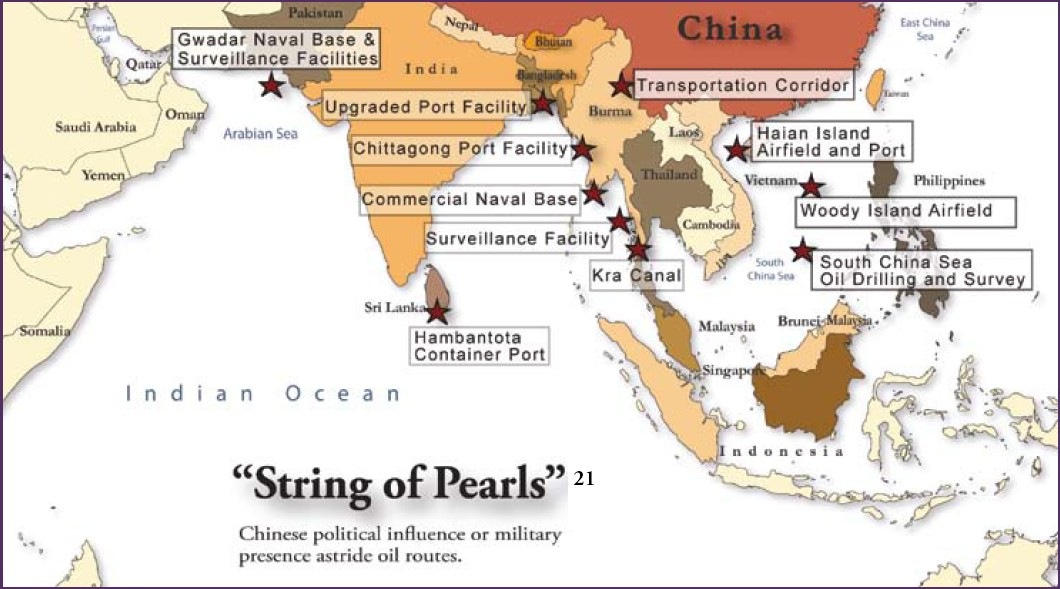

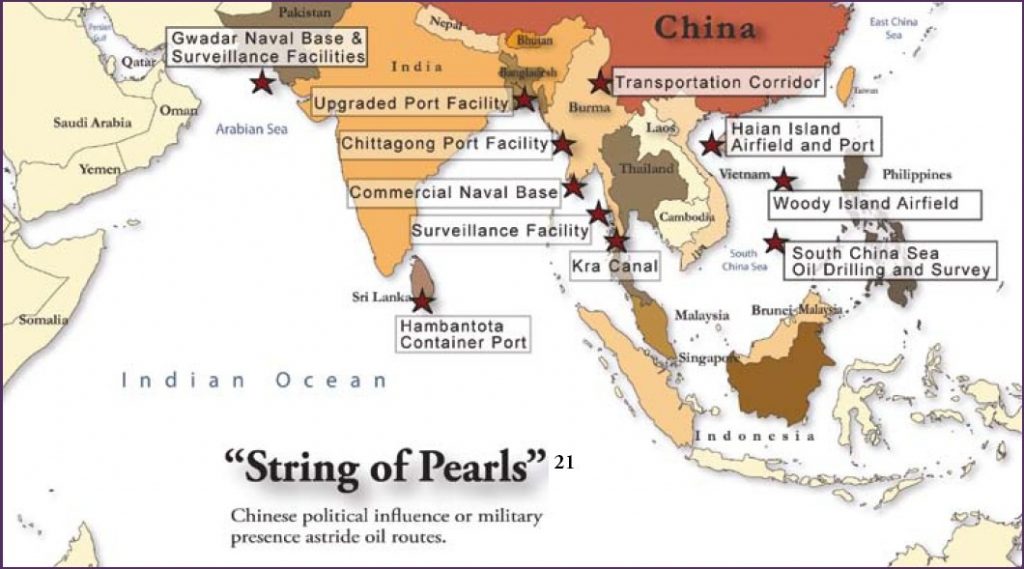

Whilst these initiatives have been presented to the international community as means to establish stronger trade links via maritime routes and promote connectivity projects in the region, most states, in particular, the US, have seen it as an extension of their expansionist policies to alter the global power structure. For regional actors such as India, as Dr. B. Chakma concludes, the BRI connectivity projects are viewed to endanger India’s historical influence over the South Asian region and the Indian Ocean, hence decreasing its geopolitical capacities.

It is important to note that while China has increased its economic presence through the BRI projects, military cooperation amongst the smaller South Asian (SSA) countries has been limited. Arguably, the lack of regular joint military exercises reaffirms Beijing’s narrative of the BRI as purely a means to expand new investment opportunities and build economic links to its Western region through supply routes from Central Asia, the Middle East and beyond.

Indeed, the government is keen to highlight that much of its development projects are protected by Chinese private security companies (PCSs), which presumably is to draw attention on the public-private sphere divide.

Whilst this divide would normally imply a limitation on state power given the presence of private actors, in the case of China, the lines are often blurred. As a result, when it comes to projects related to the BRI, by using an intermediary actor such as private security companies, Beijing is able to expand its geopolitical power and presence in the host countries without endangering diplomatic relations or alienating potential allies. Moreover, employing private security firms provide Beijing with a certain legal leeway to operate in host countries given the general lack of oversight and accountability of PCSs.

As for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), President Xi Jinping appears to focus modernization efforts towards the creation of a ‘world-class force’, with an increased emphasis on maritime capacities, catalyzed by China’s turbulent history with Taiwan and the continued territorial tensions in the South China Sea. On one hand, transforming the PLA from a largely ‘territorial force’ to a maritime power can be viewed as an example of Chinese commitment to strengthen its economy by securing trade routes and increasing regional cooperation.

On the other hand, China’s ambitions to become a sea power nation aligns with the notion of Beijing advancing its political agenda through BRI projects. This maritime strategy, otherwise referred to as the ‘string of pearls’ strategy, permits China to develop energy supply lines, increase trade with the ASEAN bloc and perhaps most importantly, to challenge US and Indian interests in the region.

One of top beneficiaries of China’s BRI policy has been Sri Lanka, a small island that coincidentally holds enormous value in its strategic positioning in the Indian Ocean. After a civil war that ravaged the country for years, foreign investment was essential to rebuild the country’s infrastructures. One such project included the creation of the Hambantota Port, financed largely by China as part of the BRI agreement in the form of loans.

In 2017, China’s influence increased further when the Sri Lankan government was obliged to hand over 70% of the port to China Merchants Port Holdings Company Limited in the form of a 99-year lease. Since then, the Hambantota Port has become a cautionary tale to many of China’s BRI partners. It highlighted the extent to which the BRI projects could endanger the host country’s sovereignty as well as drawing attention to China’s position vis-à-vis Western institutions, most notably the World Bank.

Indeed, as past years have shown, in the African and South Asian regions, countries such as Sri Lanka have shown to be more favorable to Beijing as opposed to traditional institutions rooted in the West. This preference is largely present amongst ‘transitioning middle-income countries’ where development and growth is expected but access to grants and concessional loans to finance the necessary infrastructures are limited as a result of their newly-awarded middle-income status.

In contrast, Chinese presents itself as much more lenient, whereby investment for instance, is not dependent on the recipient country adhering to certain stipulations, more precisely, policy prescriptions on a national level. These conditions are often perceived to infringe sovereignty while advancing the liberal capitalist agenda associated with the West, in particular American interests.

Nonetheless, it is equally important to note that even though these BRI infrastructure projects are presented as a unique opportunity for middle- and lower-income countries, there is an unspoken expectation that Chinese companies will be contracted to oversee the development of critical infrastructures, hence ‘entrapping’ the beneficiary state in a vicious cycle of dependency.

In a similar fashion to the Hambantota Port, Djibouti is also predicted to lose control of the Doraleh Container Terminal, a joint venture under the wider umbrella of China’s BRI infrastructure projects. Suffice to say that such a scenario would not only permit China to position Djibouti as the linchpin of its Belt and Road Initiative but to equally boost its military standing in the country. Djibouti, albeit being China’s first overseas military base, is also home to the Americans. Unsurprisingly, the increased economic links and military presence in the country have not gone down well with the Americans.

This East African state enjoys a direct view of a busy international shipping lane, and its strategic positioning was described by Mr. Zengxiang, a top official of China Civil Engineering Construction, as ‘the point of origin to freight goods across Africa’.

However, this is not to say that China’s BRI projects have been a total success. The long- and short-term economic viability of its projects have often been questioned. For instance, Beijing has had to renegotiate the rail link contract with Malaysia, bringing down the price of the project by a third.

There has also been pushback to the use of private security firms, as they have little accountability in the international and domestic scene. Whilst the problems with the private security sector are not unusual, in China’s case, it is particular since most of these firms recruit almost exclusively PLA veterans. It is thus hard for Beijing to respond to critics who view the BRI as a means to expand Chinese influence with little to no oversight.

China’s slowing economy has also limited the quantity of resources available to invest in overseas projects. According to a report by The Jamestown Foundation in 2018, BRI lending by major Chinese banks has fallen by 89%. The situation has only been exacerbated by the current global pandemic; the manufacturing supply chains have slowed down which has led to a reduction in good flowing out of China.

This is problematic because the BRI projects depend mainly on Chinese materials and supplies, and not local resources. Quarantine restrictions have had an equally negative impact on Chinese labor working overseas on BRI projects, where access to foreign building sites are restricted thus slowing down current projects in the participating countries. For example, in Sri Lanka there has been major disruption in Government road and apartment construction projects involving Chinese contractors.

More vulnerable countries such as Cambodia and Laos, who, as Fitch Solutions notes, are ‘heavily dependent on Chinese patronage’ fear antagonizing Beijing by imposing quarantine restrictions on labor, thus increasing their vulnerability in the face of COVID-19. As a recent report from Baker McKenzie notes, COVID-19 has pushed BRI governments to rethink their ‘overdependence on one country [China]’.

To conclude, it is crucial for the West, to not underestimate China’s desire to occupy America’s seat in the world stage, especially in the current post-pandemic society. For President Xi Jinping, the Belt and Road initiative represents not just an opportunity to strengthen the Chinese economy, but also a lever to promote political influence. Hence, it is highly unlikely that Beijing will abandon its BRI projects in the near future, even if it might be at the detriment of its own economy.

* Navomee Ponnamperuma is recent Warwick graduate in Politics, International Studies and French.