BY: Paul Cochrane

PEJOURNAL – The theory of peak oil, whereby the cost of extraction would exceed how much consumers were willing to pay while demand outstripped supply, was first floated more than 60 years ago. Oil production, geologist M King Hubbert predicted, would peak by the turn of the millennium.

That didn’t happen – but the spectre of peak oil raised its head again in the mid-2000s, in part pushed by Matthew Simmons’ book Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy.

Simmons argued that Saudi Arabia had inflated its colossal oil reserves – a point that has some credence, as further highlighted in Wikileaks US diplomatic cables from 2011 – with some 90 percent of Saudi’s oil coming from seven giant oil fields, of which three are more than 50 years old.

With the level of reserves questionable, particularly from one of the world’s top producers, and demand constantly rising, oil prices would rise ever higher.

Prices did indeed surge, reaching more than $140 a barrel in 2008. Peak oil theories played a part in the speculation that drove up prices. That same year, some observers were forecasting oil at $200, even $500, a barrel. Several even predicted the subsequent implosion of civilisation and World War Three.

But high oil prices and pressure to move away from an over-reliance on oil propelled a global move towards renewable energies. More than a decade later, the oil price is around $40 a barrel – and there is plenty still under the ground, largely due to enhanced oil recovery technologies, particularly for shale oil in the US.

Oil: Peak demand

There is arguably more oil than can ever be utilised. Yet is is no longer peak oil that is being forecast, but that demand for oil is peaking.

This could be bad news for oil-export dependent countries. Low oil prices and lower demand means economic problems ahead, especially in the longer term, unless diversification efforts are seriously ramped up.

For the wealthier Gulf countries, dwindling oil revenues will tighten budgets and may affect the social contract between citizens and monarchies, which have used petrodollars to maintain stability. Oman and Bahrain are already struggling with low oil revenues. Saudi Arabia’s large population puts pressure on its budget despite being a top global oil producer.

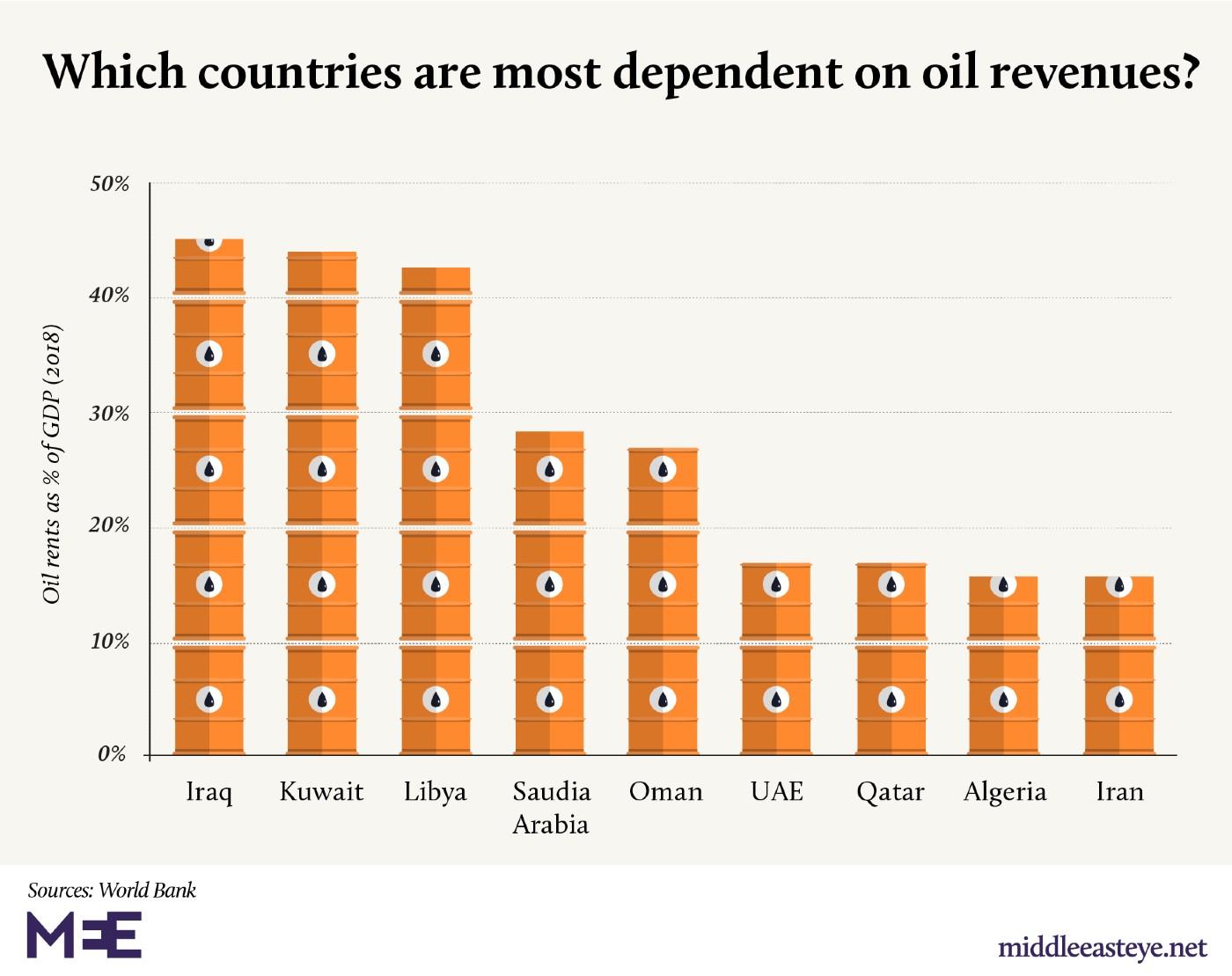

The UAE and Qatar have smaller populations, are more economically diversified, and have a high per capita wealth to better weather the energy transition. Kuwait meanwhile is an outlier, with its heavily reliance on oil revenues (42 percent of its GDP) and lack of any intent towards energy diversification.

For the more populated, less wealthy oil producers of Algeria and Iraq, any drop in oil revenues impacts public spending and the economy. Iraq is particularly vulnerable: its oil revenues account for 45 percent of its GDP, which is focused on rebuilding the country. The region’s other oil producers are war-torn Libya, Yemen and Syria.

Any increase in the use of alternative and renewable power cuts into oil revenues

BP’s recent Energy Outlook 2020 report explored what different energy models may look like until 2050, given that oil demand is on a slippery downward slope with the rise of alternatives. It envisaged three scenarios: a rapid transition away from oil; net zero carbon emissions gradually met over the next 30 years; and business-as-usual.

Pushing the transition is the pledge by more than 120 nations to set a target of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, the dropping costs of solar and wind energy, and the growing electrification of the transport sector.

“There is a cultural and political shift going on, with societies waking up to the fact that carbon emissions are damaging to the environment, and that also has business implications,” says Christian Henderson, lecturer in Modern Middle East Studies at Leiden University.

Global demand for renewables is forecast to grow by 5.7 percent a year to 2050 under the business-as-usual scenario. The net zero scenario puts it much higher, at 8.5 percent.

The Middle East holds 48.1 percent of the world’s oil reserves, according to BP, of which the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries accounts for 29 percent. Therefore any increase in the use of alternative and renewable power in the global energy mix potentially cuts into oil revenues as demand declines.

MENA renewables?

But the MENA is not yet hedging against a major change in the energy mix. Globally, the region only trails Central Asia in using renewables as a primary energy source, at just 0.3 percent of production, according to BP figures.

Outside of the GCC, regional forays into renewables have been limited to just a handful of countries, primarily non-oil states like Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt.

“A lot of countries have left it too late to start,” says Kate Dourian, a fellow at the UK’s Energy Institute. “Iraq hasn’t taken advantage of it, and Algeria was supposed to lead the effort in the region but has been overtaken by Morocco, although it depends on oil and coal for power production.

“Egypt has the advantage of attracting a lot of investment from institutions – the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the IMF – for solar and wind projects,

The region has also had its share of renewable white elephants, dating back to when oil prices were in triple digits, such as Desertec and the Mediterranean Solar Plan initiative.

Launched in 2009 to much fanfare, Desertec was intended to create massive solar power projects in the Sahara for regional use and to provide Europe with 15 percent of its power by 2050. Both projects failed.

In March 2018, Riyadh announced it would invest $200bn in solar power, but by October the project was scrapped.

Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, launched in 2006, was intended to be a sprawling carbon-neutral, waste-free development, but the $22bn project was soon scaled down to less than a third of the size. It did, however, get the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) to be based in the city in 2009.

“There is a show-off element as well [to investments in renewables],” says Eckart Woertz, director of the GIGA Institute of Middle East Studies at the University of Hamburg. “It is no coincidence that Masdar was launched before attracting IRENA.”

Oil prices have cratered and do not look likely to bounce back into the higher double digits

Yet unlike a decade ago, or even last year, oil prices have cratered and do not look likely to bounce back into the higher double digits. Renewables are once again being taken more seriously.

Across the Middle East, some $150bn is being invested in solar power, and $28bn on wind, waste-to-energy, hydro and geothermal power plants, according to MEED.

The majority of the renewable projects are occurring in the oil-producing Gulf. The UAE is leading, with 70 percent of all installed renewable capacity, while Saudi Arabia has just entered the market. Kuwait however has made no such moves.

Woertz says: “Renewables is still quite limited in the Gulf compared to Europe. They haven’t walked the talk so far. I think it will come. The economics are basically lined up in favour of renewables.”

Plans for diversification

The GCC has now realised that renewables are an inevitable part of the future energy production mix, just like the oil majors, which are also investing in the sector (BP aims to be net zero by 2050). In addition to local developments, Gulf investors are involved in solar energy projects across North Africa and in Jordan.

“It’s not about environmentalism or sustainability – yes, they can use it to legitimise and promote projects – but it’s about business,” says Henderson. “The problem is that it’s a fundamental contradiction having these oil-producing countries invest in solar energy. It’s a bit like Microsoft switching to Apple computers. You are also potentially weakening and undermining the oil market.”

The Gulf’s foray into renewables can, however, be considered as a form of economic diversification, to enhance expertise and create new revenue streams, while also reducing domestic use of hydrocarbons to enhance export revenues.

Renewable energy itself is not overly crucial for local usage, particularly given the abundance of natural gas, and potential investments in nuclear power. The UAE’s first nuclear power plant started this year, while Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Egypt have all announced plans to develop nuclear energy.

“The domestic energy transition is less important for the GCC’s economic future than the global one,” says Steffen Hertog, a Gulf specialist at the London School of Economics. “It helps to liberate some oil for export but most of the oil revenue will be determined by international forces.”

The GCC, with the exceptions of Bahrain and Oman, are in a strong position even as global demand for oil weakens. Gulf oil producers have the lowest extraction costs in the world, and some of the lowest carbon emissions in the production cycle.

With decarbonisation at source being pushed, Gulf states will be able to retain or even expand their share of the oil market as more expensive and more pollutive producers are squeezed out of the market.

“It is not the end of oil,” says Dourian. “Peak demand means there will not be demand growth, so it’s not like the use of oil and other hydrocarbons in the energy mix will fall off a cliff.

“What has been realised, even before the BP report and all these apocalyptic-type articles, is that oil producers need to clean up, to decarbonise at source. There will be demand going forward, but it will not be the 1.5 percent annual growth previously forecast.”

The shadow of Covid-19

The big question is whether the economic ramifications of the Covid-19 pandemic will accelerate global moves away from fossil fuels or if the transition will be delayed as funds are diverted to prop up ailing economies. It is also not clear to what degree new energies, such as hydrogen, will take off, as well as the electrification of transportation, which requires energy production.

“Oil demand is plateauing at the moment, but if there is a decline, spaced out over time, there are a lot of unknowns,” says Woertz.

The region has not cut back on investments in the hydrocarbon sector, with $652bn worth of oil, gas and petrochemicals projects planned or underway, according to MEED Projects. What is at stake in the future is whether countries can increase their economic diversification as oil revenues drop, and what impact this will have on societies which are used to living off petrodollars.

“It’s clear that Gulf producers will be among the last men standing on the oil market before it becomes obsolete as a fuel,” says Hertog. “They will definitely grow their relative market share and might even have opportunities to increase the absolute one.

“Set against continued population growth, that probably still won’t be enough to maintain the current social contract indefinitely, but it could help stretch out the transition.”