BY: Jacobien van der Kleij and Michael Robbins

PEJOURNAL – One of the major events that characterized the early Trump presidency was the U.S. trade war with China. From a monetary perspective, the trade war with China was not beneficial to the U.S. dollar, and hitting China with such tariffs showed the U.S. that other countries can, and will, step in when needed.The actual “war” aspect is an editorialization, but the events were still meant to show the world that when two superpowers compete for better trade deals, there is never a clear winner.

The rhetoric started on Trump’s campaign trail if we recall correctly. His speeches were filled with anti-China messaging, namely that America “was always getting beat by China”. This was a hallmark of his campaign. He came out as the strongman prepared to do something about it, although as we now know doing something about currency manipulation is an incredibly difficult task. The global economy is complicated, and you cannot bully China into submission.

However, some of the rhetoric that Trump was spewing at the time turned out to actually make sense—namely the fact that the old rules the WTO had established for China’s developing country status, when they became a member in 2001, allowed the Chinese to unfairly trade with the world as they ascended in power/GDP status, and no longer classified as truly a developing economy.

The Trump Administration thus decided they were not going to appease China anymore, and tried to wage a trade war by hitting them with tariffs, and eventually stopping exports to China for goods needed in international supply chains. Let us recount the story of the soybean crisis to illuminate how this played out.

In one move in 2018 Trump decided that U.S. farmers were no longer going to sell their soybeans to China. This was a bullying tactic meant to hurt China as Chinese imports of soybeans are used for a variety of purposes, but mainly as feed for cattle and the agricultural sector that China benefits immensely from. When the supply of U.S. soybean stopped, the Chinese simply upped their supply from Brazil, a leading soy producer of the world, thus showing the U.S. that China cannot be bullied into submission.

Lessons learned?

From a monetary perspective, the trade war with China was not beneficial to the U.S. dollar, and hitting China with such tariffs showed the U.S. that other countries can, and will, step in when needed. Hegemonic power over currency for soft power in a globalized arena is not something you can “win” in a trade war.

It is something that evolves, though, as we’re seeing more and more today. That is because other global events shape exchange rates, such as the fact that the EU was finally starting to see the light at the end of the tunnel after many tumultuous years of providing liquidation for Greece and other southern European economies. In fact in 2017, the EU hit an unexpected growth rate of 2.2 percent.

In addition, domestic policy in 2018 did not help the greenback either. In 2018, the Trump administration passed tax cuts that were supposed to spur the “buy American philosophy” and amplify consumer dollars being spent in the country. But this was hardly the case.

For example, looking at the two main policy objectives of the TCJA (Tax Cut and Jobs Acts), the top individual tax rate dropped from 39.6 percent to 37 percent, and numerous itemized deductions were eliminated or affected as well. The TCJA also cut the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent effective in 2018.

The passing of the TCJA instead helped lead to the further erosion of the greenback, relatively, for that fiscal year. This is because the extra savings that middle and rich earning families in the U.S. benefited from via the new rates were, and still are, being used to buy more foreign made products. The iPhone is a perfect example.

So are cars manufactured along an East Asian supply chain. Smartphone parts in general are not just made in China, but also Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Thus the TCJA did not spur the greenbacks nominal value, but led to a series of events producing more net profits for foreign owned enterprises.

Currency war or drama?

Thus we have arrived at an understanding of the drama currencies and politics can create. You cannot bully your way into a better exchange rate, and you have to understand the international factors at play before making policy decisions.

The funny thing is that exchange rates are actually not supposed to invoke drama—they are supposed to provide stability to the international financial system. A poor country with a weak currency can get ahead, and perhaps ought to be able to, with an export led growth strategy. But rich countries cannot do the same because their GDP growth rates are sluggish—which is precisely where the U.S. and China are at, right now, in 2021.

Two years ago Donald Trump rejected the notion that countries should be free to set monetary policies aimed at generating sustainable growth. Other superpowers disregarded his stance and continued to weaken their currency for better trade options. Today, a new sitting President in the oval office, a centrist, is likely to take the opposite stance. But this does also doesn’t make the greenback better off.

Joe Biden wins, the dollars drops

Trump’s victory in the presidential election four years ago was partly due to his promise to make it easier for American companies to do business across borders. He tried to do this by introducing import duties, which eventually led to a complete trade war as discussed, with China. Under Biden, the US faces renewed trade pressure.

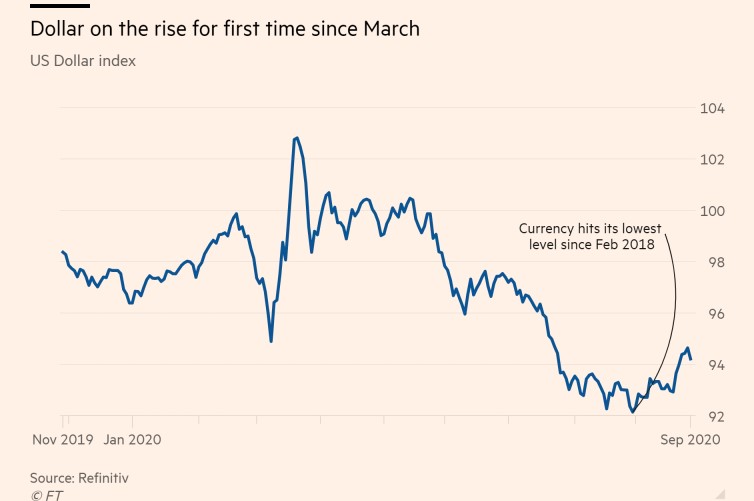

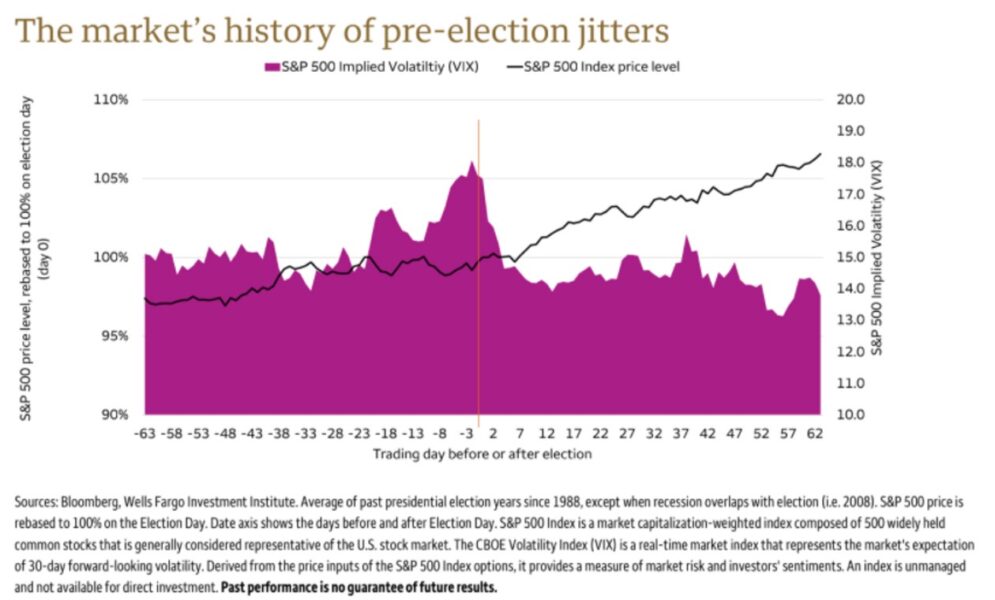

During the final hours before Election Day, the dollar swayed with the potential victory of either Biden or Trump. The currency suddenly skyrocketed in the hours following the close of the ballot boxes, as it looked at that moment as if Trump would have a surprise victory. The election had suddenly turned into quite the tight race with the dollar bouncing back and forth. Since 1980, the US dollar has risen between 2 and 12 percent every year following a US presidential election since 1980, except in 2008. Expectations of volatility can rise by 20 percent prior to the elections.

But why did the dollar drop when Biden won?

Some experts believe that if Biden has his way with his Covid-19 economic recovery, the US government debt will rise by nearly 6 billion by 2030. His economic recovery plan is expensive—1.9 trillion dollars worth. That money has to come from somewhere and generally currency exchange rates do not flourish when such a recovery plan is underway.

Since Biden was declared the winner of the election, the weakening of the US currency has spiked to 2 percent against the euro on a weekly basis. This eventually still leads to the fulfillment of Trump’s ultimate wish: a fall in the dollar that strengthens the international competitive position of American business. But will the dollar be able to flare under Joe Biden, who is unlikely to continue Trump’s bombastic trade policy? The future is his.